Every historical site is contested. Where some people seek comfort in their “heroes”, others see warmongers and murderers. Monuments like the one to General Karl Eibl celebrate a glorious military past, making it possible to forget the crimes that the Wehrmacht committed, especially in the Soviet Union. The monument to the sappers of the First World War has repeatedly been a gathering place for right-wing and far-right groups.

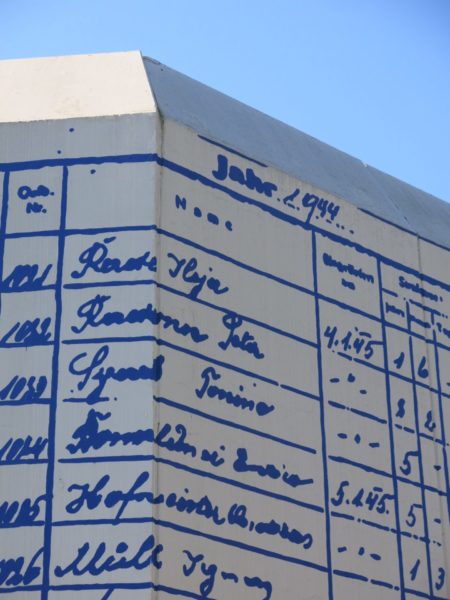

Remembering and memorialising involve conflicts about history and about our image of ourselves. This became obvious after the Second World War, when the Soviet occupation authorities ordered that the bodies of the Red Army soldiers who had died in the prisoner of war camp STALAG XVII B be reburied in the heart of the city of Krems. By turning the central square of the city into a cemetery, they wanted to create a daily reminder for the citizens of their complicity in these crimes. The monuments to the Greek and Polish victims of the massacre in the Stein prison in April 1945 are further memorial sites that urge the citizens of Krems to take responsibility for their own history. And this is needed, because memory fades away. The poetic forces at work in history in the city of Krems are emphasised by contemporary artists and their works. For example, the 105 carpet pictures that Iris Andraschek painted on the pavement in front of the former homes of expelled Jewish women show the ways in which remembering and forgetting interact with each other. The artist used lime-based paint for this. The footsteps of passers-by and the rain will make these images slowly fade away, just as we would forget without constant prompts to critically remember.

Since the 1980s it has mainly been private initiatives that have kept the engagement with the history of Nazism in Krems alive. Since 2019 the Historians’ Advisory Council has been making its proposals to the local council, which has launched a series of initiatives for critically engaging with history. There are interventions into historical images: for example, an explanatory board next to the Karl Eibl monument that points out precisely the historical contexts that the monument itself tries to make people forget. Naming is also an important area of critical history work. A park in the historical quarter of Stein is now called the Hedwig Stocker Park, thus keeping the name of a principled prison warder in the public memory. And the removal of the Nazi poet Maria Grengg from the name of a street and her replacement with the educationalist Margarete Schörl signals a critical engagement with our own history. This process too can involve a wide range of conflicting interests, as shown in the name of Franz-Zeller-Platz. When the new museum was opened here, some wanted it to stand in a “Museum Square” (Museumsplatz). The original street sign that bears the name of a Communist resistance fighter remains over only a small patch of grass.